At the start of the 1960s, when most computers occupied an entire room, the world’s programmers could barely fill a baseball stadium. Only a few thousand specialists could wrangle arcane coding languages such as Fortran and Cobol, and the unwieldy mainframes they ran on.

By the mid-1970s, there were millions of programmers. Computing’s first step into the mainstream was driven by the work of Thomas Kurtz, who died this month at the age of 96, and his fellow Dartmouth College professor John Kemeny. In 1964, the pair created a simple, fast and intuitive programming language called Basic. “It was the first effort in the history of computing to try to bring computing . . . to the masses,” he recalled in a 2014 documentary.

“All of us who have written code in the past 60 years can thank Thomas Kurtz,” said Bill Gates, Microsoft’s co-founder, who as a teenager created his first computer program in Basic and launched Microsoft in 1975 with a version of Basic for microcomputers. “In the 1960s, when computers were massive, expensive and only available to scientists, he believed everyone should have access.”

From the start, Kurtz wanted to create a system that even humanities students at Dartmouth could use with just a couple of hours’ instruction. Basic — which stands for Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code — replaced the inscrutable commands of other coding languages with ordinary English words such as “LET”, “IF” and “THEN”.

It was developed alongside another innovation by Kemeny and Kurtz called “time sharing”, which allowed several people to use a mainframe computer simultaneously. Together, these ideas paved the way for the personal computer revolution of the 1970s and 80s, as well as the cloud computing industry that followed decades later.

Born in 1928 in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park, Kurtz trained as a mathematician, receiving his PhD from Princeton in 1956. That year, he was hired by Kemeny to teach maths at Dartmouth, where he would stay for nearly 40 years.

When Dartmouth got its own computer in 1959, Kemeny and Kurtz wanted it to be something everyone on campus could use. MIT was already using the concept of time sharing for research: instead of “batch processing” each job in full, time-sharing systems ran multiple jobs for one second at a time. Kurtz’s insight was to tap this for educational purposes, which he said was a “completely nutty idea” at the time.

Dartmouth’s first computer wasn’t capable of running a time-sharing system but Kurtz and Kemeny started hand-coding one, recruiting undergraduates to help. Kurtz’s edict to the students was: “In all cases where there is a choice between simplicity and efficiency, simplicity is chosen.”

If the Dartmouth time-sharing system was the forerunner of today’s operating systems, Basic was its first app. Its brilliance was in its instantaneity: a simple Basic program could produce a response in just a couple of seconds.

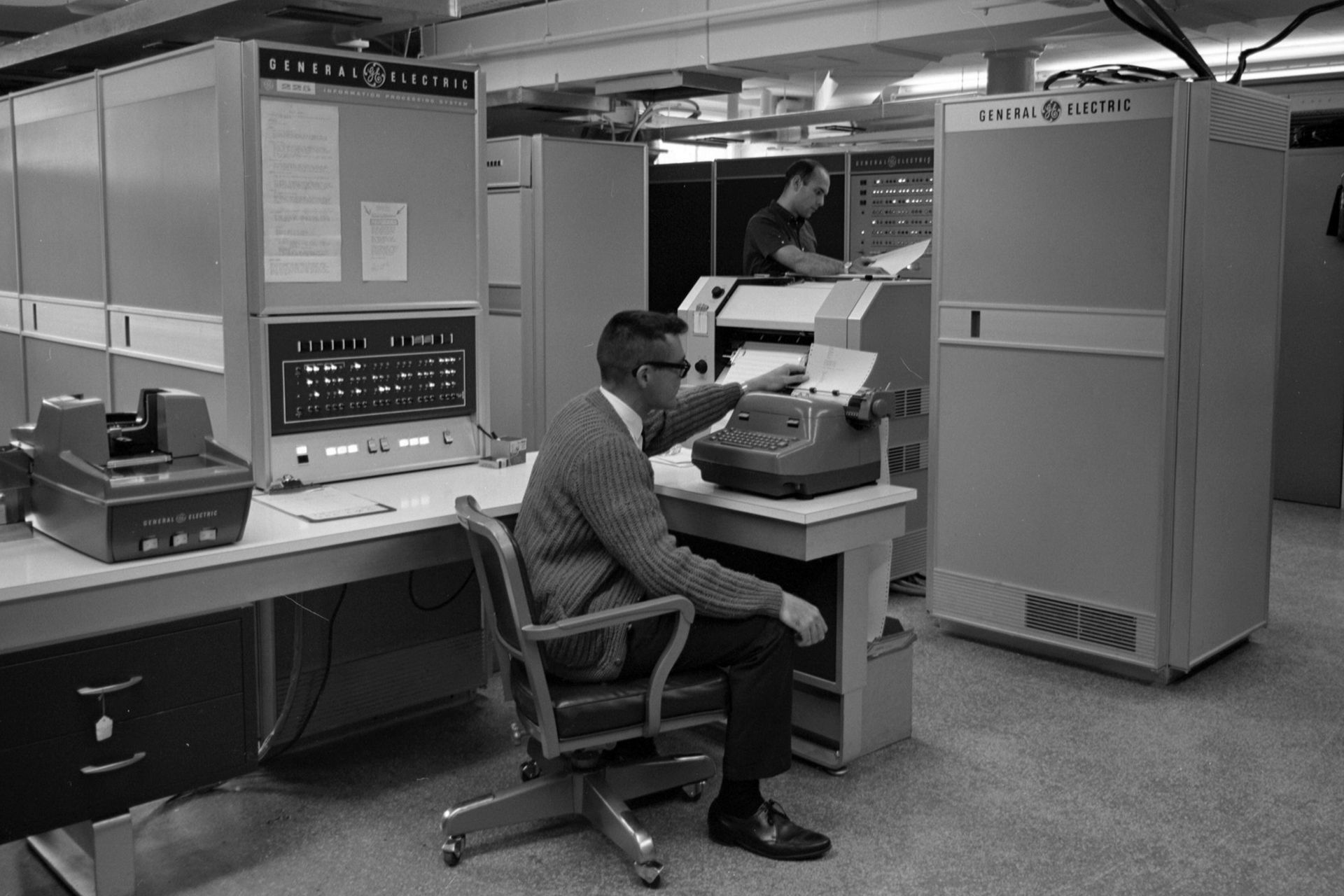

An early morning test on May 1 1964 proved that both systems worked, when two Basic programs ran simultaneously on Dartmouth’s new General Electric mainframe using time sharing. Kurtz soon hooked it up to teletype machines around campus, which could send messages to the mainframe and then print the responses. Hundreds of students were soon using it and the Dartmouth network was later extended to universities around the US, via telephone lines.

“This notion of remote access, which predominates computing nowadays, aside from PCs . . . Tom was at the forefront of seeing where that was going to go,” says Stephen Garland, who met Kurtz while an undergraduate at Dartmouth and later became a professor there, steering development of the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System and Basic.

Kurtz believed 5mn people already knew how to write Basic by the time Microsoft launched its version for the Altair 8800. Many more versions followed, including by IBM and UK computer-maker Acorn, whose BBC Basic was used in many British schools in the 1980s.

While Kemeny, who died in 1992, has been the better known of the two, Kurtz deserves recognition as an “equal partner”, according to Garland.

The two professors foresaw that computing would be so widespread that universities needed to help their students understand it. “They realised that decisions would have to be made about computer use in society and it was better that large numbers of people understood what computing was,” said Garland, “so they were not taken in by jargon or the idea that the computer was always right.”