Mikhail Gorbachev, who has died aged 91, was the last leader of the Soviet Union and its first and last state president. Although he ruled in Moscow for less than seven years, the consequences of his tenure rewrote the global order at the end of the 20th century.

During his years in the Kremlin, from 1985 to 1991, he ended one-party communist rule in the Soviet Union, halted the global arms race and allowed the peaceful liberation of the states of central and eastern Europe. His policies terminated the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and ended the cold war but led to the collapse of the Soviet empire in the process.

Lauded in the west as a hero and awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990, he was and still is condemned by many in Russia for wrecking its economy and putting paid to its superpower status. In reality, he attempted to reform a system that was in terminal decline, and thereby triggered a revolution that he could not control.

In contrast to his predecessors, Gorbachev was articulate and charismatic. He was also a brilliant tactician in the politics he knew best: manipulating the party. His instincts were democratic but his experience was bureaucratic. He was a pragmatist who could never quite bring himself to abandon his communist roots and throw in his lot with the most radical reformers. As a result, he ended up despised by diehard conservatives and liberal democrats alike.

Gorbachev was an outstanding student of the Soviet system — the first party leader to have attended university, followed by a stellar career through the party bureaucracy. Yet he eventually dismantled the totalitarian state created by Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. As he wrote in his autobiography in 1995, he was “a product of the nomenklatura [the party elite] and at the same time . . . its grave digger”.

Unanimously elected as party general secretary in 1985 when aged just 54, he was the first relatively young and vigorous leader of a system ruled for decades by elderly men. Although his elevation was regarded with initial suspicion in Washington and other western capitals, it signalled the start of a “second Russian Revolution” that proved unstoppable.

Gorbachev embarked on what he called perestroika — restructuring. The slogan was chosen to sound unthreatening. The intention was to reform the communist system, to make it more efficient and humane. But given the stagnation throughout the economy and society, he knew it would require radical change.

On the eve of his election as party leader, he told his wife Raisa: “We can’t go on living like this.” Yet as each attempt to revitalise the economy was thwarted by an entrenched and corrupt bureaucracy, he switched to ever more fundamental political transformation that came to threaten the leading role of the Communist party itself.

Gorbachev’s greatest successes were on the world stage, where he overcame deep mutual suspicion and forged close ties with Ronald Reagan, then US president, and his successor George HW Bush. After a 1984 meeting with Margaret Thatcher, she famously concluded: “I like Mr Gorbachev. I think we can do business together.”

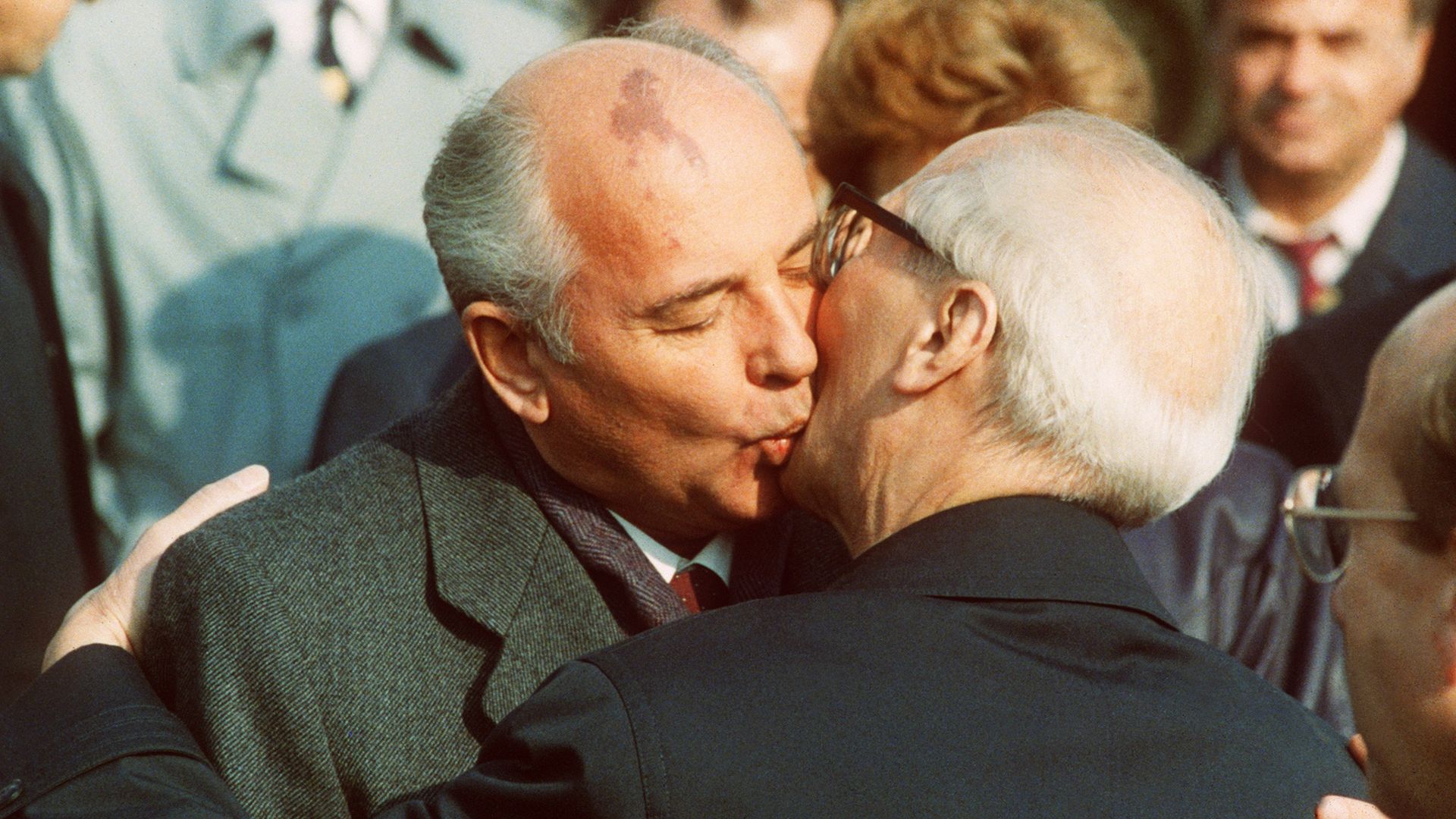

In the west, his easy smile, intelligence and charm inspired “Gorbymania” from the crowds who mobbed him on his travels with the glamorous and intelligent Raisa in the 1980s. In Germany he was most popular of all, thanks to his role in backing unification after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

His “new thinking” was instrumental in ending the ideological confrontation between east and west. Seeing a direct link between ruinous military expenditure and the sorry state of the Soviet economy, he set out to end the global arms race. He promoted the idea of a nuclear weapons-free world by 2000 and pulled Soviet troops out of their disastrous intervention in Afghanistan.

In the USSR, however, his perestroika unleashed forces he could not control. His initial popularity, boosted by televised walkabouts and frank public debates, faded as his reforms failed to transform the domestic economy and improve ordinary lives. Perestroika sought to promote private initiative without dismantling the ossified state planning system or allowing a real market economy. The result was a collapse in state-controlled production and chaos in the distribution of goods.

Glasnost, or transparency, the other pillar of his transformation process, also had unintended consequences. It was supposed to be a carefully orchestrated opening of the media to expose the sins of the past and outmanoeuvre opponents of reform. By removing draconian restrictions on information, however, it resulted in a diversity of opinion and public debate that exposed the entire power structure to devastating criticism.

When he arranged in 1986 — behind the backs of the KGB secret police — to end the exile of Andrei Sakharov, father of the Soviet nuclear bomb, he liberated a man who rapidly became the moral conscience of the country. The most famous Soviet dissident wanted genuine democracy and an end to the “leading role” of the Communist party. In 1989, at the Congress of People’s Deputies, a grudging Gorbachev gave him the platform to say so. The nation stopped work to watch them argue on live TV and, from that moment, the revolution was unstoppable.

One of Gorbachev’s greatest failures, however, was in not dismantling, or at least emasculating, the KGB itself. At first he relied on the security service to drive the reform process, but in the end it became the leading force of reactionary opposition and led the coup attempt in 1991 that sought to overthrow him. Although the coup failed, the president’s inability to revive the moribund economy and contain an upsurge of nationalist revolts that spread from the Baltic republics to the Caucasus was what eventually destroyed the Soviet Union.

What started as demonstrations for devolution to outlying parts of the empire became outright independence movements, spreading in turn to Russia itself. Gorbachev never understood why there was so much resentment of Soviet rule but his democratic instinct meant he was not ready to suppress it. Without a ruthless tsar in the Kremlin, the centre could not hold.

He also refused to intervene militarily to stop the overthrow of communist regimes in eastern Europe, espousing what Gennady Gerasimov, his spokesperson, famously described as the “Sinatra doctrine — they’ll do it their way”. He even gave his blessing to German reunification in 1990 against strong opposition from the security services. It was a sign of weakness for which the KGB, the military establishment, and communist loyalists never forgave him.

That was the year when Gorbachev was awarded the Nobel Prize for his “leading role in the peace process”. But already his authority in Moscow was fading fast. As the economy collapsed and demonstrators demanded independence on the streets of Tallinn, Vilnius and Tbilisi, he swung back to the conservatives in his party, attempting to reimpose Soviet authority. It was too late. The centre of power was moving inexorably to the Russian presidency by then held by his great rival, Boris Yeltsin.

The abortive three-day coup in August 1991 merely accelerated the process of disintegration. Gorbachev, briefly placed under house arrest in his holiday villa in Crimea, never recovered his full authority. The Communist party was banned and Yeltsin emerged as hero of the hour. The Soviet Union ceased to exist on December 25 and its last leader was bundled ignominiously into retirement.

Controversy over that imperial disintegration persists to this day. President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB colonel, is driven by the belief that the collapse of the Soviet Union was “the biggest geostrategic tragedy of the last century”.

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev was born on March 2 1931 into a peasant family in the village of Privolnoye, in the rolling wheat lands and sheep farms of the Stavropol region in southern Russia. His experience as a child under German occupation was important. “Our generation is the generation of wartime children. It has burned us, leaving its mark both on our characters and on our view of the world,” he wrote in his memoirs.

He never forgot the experience of stumbling across the rotting corpses of Red Army soldiers under the snow. “There they lay in the thick mud of the trenches and craters, unburied, staring at us out of black, gaping eye sockets.” It made him acutely aware of the futility of war and suspicious of the power of the military establishment.

Thanks to his family history, the future party leader was also conscious of the cruel and arbitrary treatment of dissent under Stalin. Both his grandfathers suffered persecution in the 1930s: one was exiled to Siberia, the other was imprisoned and interrogated by Stalin’s brutal NKVD security police, forerunners of the KGB, as a suspected Trotskyite.

He still managed to be top of his class in school and went on to Moscow State University to study law in 1950. Later he admitted that he and his fellow students were subjected to “massive ideological brainwashing”. But he read voraciously, declaring that “the first authors who sowed the seeds of doubt” in his mind about the communist system were Marx, Engels and Lenin.

Energetic, persuasive and a good listener, Gorbachev owed his swift promotion to Yuri Andropov, head of the KGB, who became his most important patron. Andropov saw his protégé as a loyal communist who would rejuvenate the leadership and clean up the system. When still under 40, he became party leader in Stavropol and in 1978 was summoned to Moscow; made agriculture secretary in the central committee, he was promoted to the Politburo two years later.

When Andropov succeeded Leonid Brezhnev as party leader in 1982 he appeared to be grooming Gorbachev as his successor. But he died and his protégé’s path to the leadership was blocked by Konstantin Chernenko, a Brezhnev loyalist determined to reverse the reform process.

In the meantime, Gorbachev had met by chance the man who became his most important intellectual inspiration for reform: Alexander Yakovlev, a former head of the party’s ideology department.

They met in 1983 when Gorbachev was on an official visit to Canada to inspect farm facilities. Stranded for hours while awaiting the arrival of Ottawa’s farm minister, they took a “walk that changed the world” and discovered that they shared almost identical ideas. Three weeks later, Gorbachev persuaded Andropov to bring Yakovlev, the Soviet ambassador to Canada, back to Moscow.

His other key ally was Eduard Shevardnadze, former party leader in Georgia, who became his inspired choice as foreign minister in 1985 — his trusted envoy throughout the process of detente and confidence-building that ended the cold war.

It was Yeltsin’s instinct to back the opposition that proved the most prescient and it was Gorbachev’s hesitation to break from his party that destroyed him. Its banning after the 1991 coup removed Gorbachev’s power base. He never forgave Yeltsin for his disloyalty.

The death of Raisa in 1996 then left Gorbachev devastated. Asked once what he discussed with his wife, he had replied with one word: “Everything.”